|

Monday kicked off a busy week here at the field station. The first session of college courses began this week while school groups and Road Scholar continued their activities. Danville High School spent Monday afternoon checking the pH and salinity of the water. The group also learned how to trawl and tried their hand at trawling a couple of times. On Tuesday morning, Covenant Christian High School students went to Wallops Island to learn about dunes. The students practiced making their own dunes out of only the materials provided to them. They also combed the beach to find shells. The students went to the Maritime Forest on Wednesday morning to walk around and observe the different layers of the forest including the dirt and trees. Students from Owen J. Roberts High School spent Wednesday morning learning about invertebrates at Wallops Island. While there, they used sieves to filter through the sand in hopes of finding invertebrates. They also walked along the beach to find shells. Road Scholar participants kicked off Thursday morning with a kayaking trip through the Assateague Channel. During their morning paddle, they enjoyed the sights and saw wildlife including juvenile bald eagles and ponies. On Thursday afternoon, students from Strayer Middle School went to Tom’s Cove to observe the environment. While they were there, they used sieves to discover what animals they could find. Also, they used what educators Hannah and Paige called a “Godzilla line” to scare animals into a net. To end the week, students from Freedom Middle School spent Friday morning in the marsh examining characteristics of the marsh environment. They embraced the setting by diving into the mud and getting a full body experience of the marsh. Students in the Biological Oceanography class with Dr. Robert Vaillancourt from Millersville University took abiotic readings of the ocean on Friday afternoon.

0 Comments

There’s no better feeling than capturing that one precious moment in nature, when a bird takes flight, a bumble bee lands softly on a flower, or the setting sun reflecting perfectly on the surface of a mountain lake. Photographs are one of the best ways to relive your adventures and an excellent tool to teach others about the beautiful wildlife you’ve experienced. But when it comes to nature photography, capturing that perfect moment can be a challenge because there are so many moving parts, and wildlife can be especially unpredictable. We asked Chincoteague Bay Field Station’s expert nature photographer and Road Scholar instructor Jim Clark to provide us with a few simple tricks to elevate your photography and bring a piece of nature home with you: 1. Know Your Subject“Be a naturalist first, photographer second. I guarantee your images will be much more appreciated and welcomed by your audience,” explains Jim. “Oh yeah, you’ll have more fun, too!” The best way to photograph nature is to understand nature. Once you gain a deeper knowledge of your subjects, you’ll have an easier time capturing those defining moments about what makes nature so awesome. 2. Don’t Just Photograph Nature; Photograph to Be in NatureYou shouldn’t photograph nature just to get a pretty picture. Professional nature photographers enjoy being outside as much as they love capturing that perfect moment. For Jim, he loves how his students and Road Scholar participants have “just as much fun watching a great egret patiently wait for the right moment to strike the water to catch a fish as they did actually photographing it.” Nature photography should be about the experience and appreciating the beauty of the world, and then about you trying to photograph it. 3. Knowing When to Anticipate and When to ChaseThis one is a twofer. Knowing when to wait for just the right moment to capture can be hard, but it’s also very important. It involves plenty of patience and having a little know-how (see above tip) to anticipate how a moment might play out. Slow down, observe and wait to see if you can anticipate something incredible about to happen. Then be ready to chase the moment. Just as important as anticipating is knowing when to chase a moment. Once you see a moment beginning to unfold, get to work capturing the moment, like an osprey diving for a fish or two polar bears wrestling on the arctic tundra. Just remember: Jim says that knowing when to anticipate and when to chase aren’t mutually exclusive. Both depend upon each other to capture that perfect photograph. 4. Capture a Sense of Place“As nature photographers, we strive to seek that elusive characteristic in our landscape photography: a sense of place,” says Jim. “After all, it is the ‘it’ factor in landscape photography to have our viewers feel as if they can actually sense being there.” That’s why truly immersing yourself into the landscape you are photographing is so important in becoming a skilled and confident nature photographer. Let all distractions fade away and try to pinpoint what makes this landscape so uniquely beautiful. Engage all your senses – savor the experience. The more connection you have with the location, the better your photography will stand out and the more your viewers will feel that magic, too. 5. Get Eye to Eye with WildlifeThough your first inclination might be to remain standing to photograph a small animal, a guaranteed technique to improve your wildlife photography is to change your perspective. Look at your subject from a different angle and get low for an up close and personal view of the animal. “What makes a lower perspective appealing? The short answer: intimacy,” states Jim. “The viewer gets a sense of looking straight into the animal’s eyes and experiencing the world as the animal does.” 6. Listen“Newly minted nature photographers tend to focus on what they see, not what they hear. They fail to take advantage of the moment they are photographing when they don’t use all of their senses.” Jim explains that there’s two reasons for listening when photographing nature. The first is to help identify the species you want to photograph. Sometimes the sounds an animal makes will reveal what it is going to do next. The second, and more important, is that nature’s symphony provides an extra level of nature appreciation. Enjoy the experience! 7. Challenge YourselfOnce you’ve become skilled at the basics of photography, step outside your comfort zone and try something new. Try a new perspective or a different lens. Experiment photographing under different ambient lighting situations. Try a new Road Scholar photography program. “Make this the year you say to yourself, ‘Maybe it’s time…’ Then, fill in the rest of the sentence, and go for it,” Jim says. “Make this the year to increase your confidence, improve your skills, and raise your enjoyment in photographing nature.” A former North American Nature Photography Association President, Jim Clark is the nature photography instructor for the Chincoteague Bay Field Station, Wallops Island, Virginia. Jim leads anywhere between six to eight Road Scholar nature photography workshops at the station. Jim is also a columnist for Virginia Wildlife Magazine, former contributing editor for Outdoor Photographer magazine and author/photographer of six books. Visit Jim’s website at www.jimclarkphoto.com or like him on Facebook. For a full list of Jim’s Road Scholar programs, and more learning adventures, visit www.roadscholar.org.

Images © Jim Clark. All rights reserved.  Sean, Bloomsburg University: Sean collected a species list of the different nocturnal amphibians and reptiles that appear on CBFS campus. Sean logged 10.5 hours of walking and searching for creatures, typically beginning around 10 p.m. “There were nine species that occur just around campus I was able to find,” Sean said. The most common find was the fowler’s toad, which Sean said he found in a variety of sizes. “This is suggestive we have a good population of endemic toads,” Sean said. Sean also identified bull frogs, green tree frogs and southern leopard frogs, as well as a black rat snake. “They’re beneficial in controlling rodent populations and Lyme’s disease. They’re completely harmless,” Sean said about the black rat snake. Taylor, Kutztown University: Taylor’s research consisted of comparing salt marsh health between Greenbackville and Wallops Island, which has a pristine marsh, in order to prove the shell berm on CBFS’ living shoreline in Greenbackville prevents the marsh from thriving. Taylor profiled the marsh then looked at factors like plant diversity and abundance, water quality and fish species, height and weight present. “Site one [Greenbackville with the shell berm] had very unstable salinity,” Taylor said, “There were only nine fish caught at site one compared to over 200 fish caught at site two [Greenbackville channel] which shows how unhealthy this site is.” Taylor said her ultimate goal is to get a permit to remove the shell berm and to create salt marsh channels to help the marsh in site one thrive. The shells in Greenbackville block water from entering the marsh and have been washing up ever since Greenbackville flourished in the oyster industry, because the people working the shucking houses would throw them into the water. Anna and Shannon, Bloomsburg University: Anna and Shannon studied vernal pools at the Chincoteague Wildlife Refuge and how the Southern Pine beetle could affect them. “Vernal pools are fresh water formed in depressions on forest floors that act as habitats to amphibians and plant life,” Anna explained. Anna said they got the idea for this research project from a former vernal pool study conducted by Bloomsburg professor Dr. Hranitz and another student researcher in 2012. In this original study, 85 pools were marked, and Anna and Sharon hoped to re-locate 30 of these and re-evaluate them. They focused on the Lighthouse Trail, Woodlands Trail and Wildlife Loop to look for habitat effects from the beetle. “The Lighthouse Trail had the least impact from the Southern Pine beetle and the Woodlands Trail had the most,” Anna said, adding they also found two new pools. Anna added they also found toads in areas that were clear cut to control beetle populations and areas that were not, and they noticed that the toads had different colored patches on their throats, which they believe could be a possible mutation. The fish and wildlife service asked the team to help them continue researching impacts of the Southern Pine beetle. Becca, Bloomsburg University: As a geography and planning major, Becca focused her research on how to properly manage and utilize Greenbackville, CBFS’ living shoreline. “There’s no plan and there’s no future right now,” Becca said. Through student and staff surveys and interviews regarding peoples’ experiences and hopes for the site, as well as its strengths and weaknesses, she was able to come up with a feasible action plan. “11 out of 11 staff members of CBFS [in my sample] mentioned funding as the biggest issue,” Becca said. With this in mind, Becca researched several grants CBFS could apply for to help Greenbackville with its weaknesses, such as removing the shell berm and invasive phragmites, and looking into making it more handicap accessible. Becca also said she hopes to see the field station get involved with the community of Greenbackville so they can learn from one another and share ideas to ensure everyone’s needs are being met to preserve the area’s history while maintaining a healthy ecosystem. “One project I think should be done would be to move the shucking house to the back marsh site because it’s about to fall into the ocean,” Becca said. Sarah, Kutztown University: Sarah used her background in geology to research how Assateague Island is crossing over onto Chincoteague Island. ”The general goal was to model past depositional environments using stratigraphic analysis of vibracores in conjunction with geophysical methods,” Sarah explained. Vibracores dig meters into the ground to collect sediment samples so the user can see an ecosystem’s history and how its environment has changed over time, and Sarah said these samples show how Assateague and Chincoteague have evolved from natural events such as storms or inlet closure. She also used Ground Penetrating Radar and Compressed High Intensity Radiated Pulse Sonar to image the area around where vibracore samples were taken to collect further information about the geology of these areas. “[This] allows us to make more educated interpretations when analyzing possible connections between stratigraphic layers seen in different cores,” Sarah said. Sarah said shell samples that get sent out to be radiocarbon dated, grain size and micro fossil analysis also play an important role in examining these barrier islands’ geological history. “Eventually, after we gather, analyze, and merge additional data we plan to model the overall formation and evolution of the duplexed barrier island system at Assateague and Chincoteague,” Sarah said. CBFS's Living Shoreline site sits at the forefront of Greenbackville, a coastal community along Chincoteague Bay. Erosion and storm surges plague the field site which is used as an outdoor classroom space for hundreds of middle, high, and undergraduate students each year. During the past year, more than 500 local students from the surrounding communities have participated in action projects at the Living Shoreline, looking at water quality, oyster growth on the Oyster Castles (c), planting Spartina, and removing invasive species. In July students, families, and community members, joined forces with undergraduate students and our staff to review some of the successes of this project. Dr. Sean Cornell of Shippensburg University helped us to kick off the day with an inspirational lecture about the historic significance of the site as well as his experience with the project. Dr. Cornell spoke specifically about his excitement of the oysters that are colonizing the Oyster Castles(c). "This is really fantastic to see. This tells me that our site can support oyster growth," said Cornell to his students during a survey of biodiversity on the castles. CBFS hosts Community Action Days a number of time throughout the year to inspire and educate people about the impacts of climate change and provide the tools and resources for those who live in coastal areas to make positive environmental change. These activities are funded by an EPA grant. CBFS also hosts a collective known as the Living Shoreline Team through their SPARK program which meets once a month to complete stewardship projects at the site. To learn more and get involved in these activities, contact Cortney Weatherby at cortney@cbfieldstation.org.

Conservation biology, an interdisciplinary study including animal identification, data analysis, environmental restoration, politics, GIS and interpersonal communication, wrapped up last week here at the field station. Taught by Dr. Aaron Haines, from Millersville University's biology department, students completed three weeks of field work including a trip to the Nature Conservancy in Oyster, VA, to learn about scallop and eelgrass restoration and snorkeling in eelgrass beds. Mike, Millersville University senior, said his favorite part of the class was the kayaking trips they went on in Shad Landing and Greenbackville. “Every outing we went on had the essential theme of biodiversity,” Mike said, adding that the class looked at factors like the types of grass growing and species of birds present in the two different ecosystems. Haines said biodiversity and species richness are the basis of conservation biology, and examining these two concepts can help determine whether an animal’s population is growing, declining or if it’s healthy. One way the class examined populations was by setting pitfalls. Senior Millersville University student Kelsey said they caught many toads in their pitfalls, and they used the method of mark and re-capture to see if the area was frequently visited by toads. “We caught the toads and put pink dye that solidifies at the tip of its toe,” Kelsey said, “It’s a good method to measure population size and density.” Kelsey mentioned one of her favorite excursions the class went on was an owl and bat survey at night on Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuge. “Something new this year, we have new technology that identifies bats by their calls,” Haines said. Haines said even though the technology isn’t necessarily perfect, it gives the user a fairly accurate identification of bats’ calls. “Three species it identified that could potentially be there were the Eastern red bat, which are pretty common, evening bat and little brown bat, which have a declining population. It’s really cool to know Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuge could potentially have a little brown bat feeding on its property,” Haines said. Millersville University senior, Maddie, said the class taught her how valuable human effort can be in conservation. “The absence or presence of one species can affect an entire ecosystem,” Maddie said. Maddie added that she learned it’s important for people of all backgrounds to be involved in conservation. “You don’t just have to be a biologist in conservation, you can do anything,” she said. Haines said he strived to teach his students not only the scientific aspects of conservation, but how to successfully work with people to meet both the wants and needs of conservationists and the public as well as legal aspects, such as environmental impact statements. “It brought it full circle that scientists need to work with the community and meet their needs while still achieving your goals,” Mike said. In honor of Shark Week, we’ve decided to debunk (or confirm) some shark myths! Sink your teeth into 10 common shark tales that are floating around to see if they’re fact or fiction.

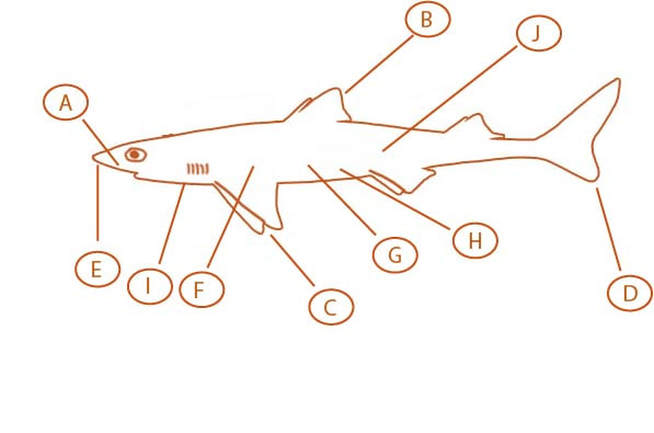

Sharks have no bones Fact Sharks skeletons are made up entirely of cartilage. This helps sharks move around quickly, because cartilage is less dense than bone, and helps keep the shark from sinking to the bottom of the ocean. Sharks commonly attack people unprovoked Fiction Sharks’ diets consist of small fish, and humans look a lot bigger than what they’re interested in eating. The chances of being struck by lightning are actually higher than getting bit by a shark. National Geographic reported you have a 1 in 11 million chance of being killed by shark in your life. However, if you do end up getting bit, sharks will typically realize you are not the food they’re interested in and release their grip quickly. Sharks only live in deep ocean water Fiction Sharks can be found in all depths of the water and some can even be found in brackish water like bays or rivers. Some that are common throughout the Chesapeake Bay include dusky sharks, sand tigers, smooth dogfish and hammerheads. Sharks are in the same family as skates and rays Fact Sharks, skates and rays are all members of the Elasmobrandchii family. To be classified into the Elasmobrandchii family, an animal must have a skeleton made up of cartilage and no bones. All sharks need to swim constantly or they’ll drown Fiction This is true for many shark species, but not all of them. Sharks breathe through their gills, and when water passes over the gill’s membranes, blood vessels pull oxygen out of the water allowing the shark to breathe. However, different species use different methods to force water over their gills. Some sharks, such as bullhead sharks, aren’t active swimmers and can breathe while staying still, but most sharks do need to swim to breathe. The biggest shark is the great white Fiction The biggest shark is the whale shark, which can grow up to 60 feet! The basking shark is the second biggest and the great white is third. The largest great white recorded was 20 feet long. Sharks can sense electromagnetic fields Fact Near the tip of the shark’s nose, its rostrum, there are small pores called ampullae of Lorenzini that gives the shark electroreception. These pores pick up electrical impulses, such as movements or heartbeats of other organisms. This is how sharks find their prey even from far away or in dark, murky waters. Sharks have natural camouflage Fact Countershading helps sharks blend in with their surroundings because they naturally have dark colored tops and light bellies. This helps them hide because if you look down on a shark from the top of the water, it’ll blend in with the darkness and if you look up at it from below, the sun shining on the water will match its bright white underside. Sharks have no predators Fiction Humans kill about 100 million sharks every year, largely because of finning. Finning is an illegal practice that involves cutting off a shark’s dorsal fin to use for cultural or commercial reasons. It’s also been said that shark cartilage can help cure cancer, but there isn’t any substantial evidence to support this claim. While in the womb, some sharks will eat their siblings Fact Multiple shark embryos in utero from different fathers can compete for survival. Typically, the largest pup will devour all of its siblings in the womb except for one. Sharks are one of the ocean’s most famous and intriguing creatures. They easily dominate portrayals of marine life in pop culture from their iconic dorsal fins to their reputations as bloodthirsty predators. Read below about the internal and external anatomy of sharks to learn about what the purpose of each of their fins are, how they hunt their prey and how some of their organ functions differ from humans.

External anatomy: A.External Nares: Near the tip of the shark’s nose, or its rostrum, these are two openings, one on each side, used for sensory activities. Water is taken up through the smaller opening, passes by a sensory membrane and then released through the larger opening. This helps sharks detect blood of prey and determine water quality. B.Dorsal fin: This iconic fin keeps the shark upright and prevents it from turning over in the water. This fin is necessary for sharks to maintain stability, however, they are often sought after in the illegal practice of “finning.” Finning involves removing a shark’s dorsal fin for human use such as making shark fin soup or using it as a home decoration. C.Pectoral fin: This fin helps the shark steer. It acts similar to wings on an airplane. D.Caudal fin: The largest and most powerful fin on the shark’s body, the caudal fin helps keep the shark from floating up without using much energy. E.Ampullae of Lorenzini: This part of the shark uses electroreception. It senses electrical impulses in the water, such as the heartbeat of its prey in the sand, and also allows the shark to read changes in temperature, salinity and water pressure. Internal anatomy: F.Liver: Taking up roughly 80% of the shark’s internal body cavity, the liver is the largest of sharks’ organs. The liver stores energy as dense oil which helps the shark with buoyancy, its ability to float. It also works as a part of the digestive system and helps filter toxins out of the shark’s blood. G.Spleen: A shark’s spleen’s purpose is to create red blood cells. In humans, red blood cells are created in bone marrow, however, sharks have no bones or bone marrow. A shark’s spleen is the main part of its immune system. H.Rectal gland: The rectal gland plays a vital role in osmoregulation, regulating the shark’s salt balance. This helps sharks stay hydrated by excreting high amounts of concentrated salt. I.Heart: Sharks have an S-shaped heart, and it pumps deoxygenated blood through its arteries to the gills where it is oxygenated and distributed through the rest of the body. J.Stomach: Shark stomachs are shaped like a J and are covered with rugae, wrinkles that increase its size digestion and nutrient absorption. Alex Wilke, a coastal scientist with The Nature Conservancy, joined us earlier this week for the third Tuesday Talk of the year. The Nature Conservancy works worldwide to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and people. One of these areas is the barrier island system found on the eastern shore of Virginia.

Known as the Virginia Coastal Reserve (VCR), these barrier and marsh islands are the longest expanse of protected coastal wilderness remaining on the east coast. Within these 45,000 acres of owned and protected land, conservation organizations like The Nature Conservancy work towards land protection, migratory bird conservation, marine restoration, climate resiliency, outreach and education. Wilke’s focus has been on the stewardship and management of migratory and breeding birds that spend time on Virginia’s barrier island system. She studies American Oyster Catchers, Black Skimmers, Terns, Whimbrels, and other shore and migratory birds, which are important to the coastal ecology of the area. Familiar with their behavior, she explained why it was important to protect the islands where they nest. For one, for many of these birds lay their eggs right in the sand. Any large human presence on those beaches would be harmful to the development of those eggs. “They really rely on camouflage, which makes conservation necessary as humans would have an impact,” Wilke said Humans aren’t the only thing these shorebirds have to worry about. Raccoons, crabs, and even coyotes prowl the beaches looking for these nests as a source of food. As mentioned previously, the birds use camouflage to avoid these predators. However, one ground nesting shore bird found here, the Piping Plover, has another unique strategy. When a predator approaches a Piping Plovers nest, the bird will fake a broken wing, flailing about in the sand away from the nest in order to draw the predator away. These birds are an amazing and integral part of Virginia's coastal ecology, and its important to continue protecting and respecting them and their habitat. For ways to get involved, please visit The Nature Conservancy's volunteer page and keep an eye out for information about the Birding and Wildlife Festival in Cape Charles, Virginia. You can find more about this event here. Our final Tuesday Talk of the year will be held on August 8th and will feature presentations from student researchers. Our Sea S.T.A.R. (Students Teaching and Researching) internships are offered to rising high school seniors and gives them hands on experience in marine science every summer. We accept up to eight students and give them opportunities to work in the field on a research project of their choice and chances to lead and educate others with our adult and family programs. Check out what our seven Sea S.T.A.R. interns are up to for their two months at the field station as they study environmental science and share their knowledge with others.

Gabrielle: Due to Gabrielle’s success in her environmental science courses at Indian Creek High School in Gambrills, MD, one of her teachers who worked at CBFS recommended she apply for the Sea S.T.A.R. internship. This is her second time visiting the field station and she looks forward to experiencing more hands-on education while researching how salinity affects the sex of the blue crabs. “I like my environmental science classes. I find it interesting and I like learning about what we can to try and stop what we started or at least slow it down,” Gabrielle said, talking about how she particularly enjoys learning about human impact on the environment and how we can live more sustainably. Heaven: As a junior summer camp counselor at Maryland’s Howard County Conservancy, learning about the environment and spending time outside during summer vacation is expected for Heaven. In her role of a junior camp counselor, Heaven helps teach children ages 3 to 13 about environmental topics like insects, marine life and water quality. Once Heaven graduates high school, she hopes to pursue a career in animal science and her dream job is to be a veterinarian pathologist. For her research project, Heaven will study starlings, an invasive species of birds. “I settled on studying them and their behavior … They’re from Europe and they were brought over because Shakespeare lovers wanted all the birds from his plays here,” she explained. Mikaela: Mikaela visited the field station last year on a field trip with Montgomery Blair High School, in Silver Spring, MD, and learned all about the intertidal zone, sand dune ecology and sustainable marshes. However, as soon as she left, she was excited to come back. “I looked to see if they had an internship here because I really wanted to come back,” Mikaela said. Mikaela enjoys her biology and environmental science classes and is considering pursuing a career in life sciences post-graduation. She looks forward to sharing her knowledge with others about environmental science and ecosystems through the Sea S.T.A.R. internship. For her research project, she partnered up with Emma to study the mortality of horseshoe crabs on Wallops Island. Melody: Future marine biologist Melody, from Wilmington, DE and student at St. Mark’s High School, returned to the field station to kick start her goal of becoming a scientist. “I’ve always been drawn to water and everything that lives in it,” she said, adding she completed an AP environmental science course last year. For her research project, Melody will investigate the different colors of coquina clam shells. “I collect water quality data and I collect a bunch of shells and record their color and then I’m going to try and find a correlation between that,” Melody said. She added that if she cannot find a correlation within her data, she’ll see if local predators play a role in their color. Cameron: Visiting the field station from Barstow, CA, Cameron aspires to be a park or a forest ranger in his future. “I do a lot of community cleanups and I’d like to work in sustainability or environmental preservation,” Cameron said. He added his passion to lessen human impact on nature drives him forward in his environmental activism and future after high school. For his research project, Cameron is looking at different ways to kill phragmites, an invasive species in local marshes, so spartina alterniflora can grow. Cameron added he also enjoys acting as a mentor to the field station’s summer camp kids. “I like working with the kids and helping them learn about different organisms in the ocean,” he said. Emma: As an aspiring animal scientist, Emma was drawn to the Sea S.T.A.R. internship to fulfill her advanced program requirements as a senior at Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring, MD. Emma wants to study either marine biology or pre-veterinarian after she graduates. “I’ve always loved animals and science, they’ve been a constant throughout my whole life,” she said, “There’s so many species we don’t understand. I think it’s interesting how much we don’t know.” For her research, Mikaela and she are looking at the mortality of horseshoe crabs on Wallops Island. Matt: Matt is an ocean and science enthusiast and he’s excited to be at the field station for his first time. A student at Terre Haute South High School in Terre Haute, IN, Matt grew up with a passion for marine life. He’s gone on snorkeling and scuba diving trips in Mexico with his father and maintains his own aquarium at home, which houses a yellow watchman goby, soft corals, a stony coral and clownfish. Matt wants to pursue marine biology after high school and is particularly interested in specializing in coral reefs. For his research, Matt will be analyzing recent trawl catches and compare these findings to former catches and data from a few years ago. “I’m looking at bony fish populations and how factors like pH and salinity change over years,” he said. |

About

Everything you need to know about CBFS's educational programs, visiting Chincoteague Island, and more! Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed