|

Jay Ford, Executive Director of the Virginia Eastern Shorekeeper Organization (VES), presented our second annual Tuesday Talk to our college summer session students last week.

VES is a chapter of the international Waterkeeper Alliance which is an organization that fights for clean water for all and strives to hold polluters responsible. “Everything we do revolves around access to clean, swimmable, drinkable water. We see it as a human right,” Ford said. Ford explained that the biggest water polluters on the Eastern Shore are confined animal feeding operations (CAFO). A CAFO is a farm that mass produces meat with 50,000 birds to one house. Ford said that the CAFOs Perdue and Tyson are the top two polluters in Accomack County. “Between the two of them, they make up 97 percent of the pollutants in Accomack County,” Ford said. Perdue discharges significantly more waste than Tyson does into the Atlantic Ocean, however, Ford said Tyson dumps waste into the Pocomoke. “Tyson is currently in a consent order process with the state of Virginia for violating the conditions of their general permit,” Ford said. A general permit allows big companies to pollute a small, specific amount without being sued, but Ford said Tyson has gone over that limit discharging antibiotic content into the Pocomoke. CAFOs not only impact water quality, but also air quality. “The National Air Emissions Monitoring Study data show that no farms meet EPA’s Clean Air Act threshold for particulate matter,” Ford said. A farm cannot be sued though under the Clean Air Act for not meeting these standards because of exemptions granted under the Bush administration. “Making sure this industry is held accountable and a good neighbor out here is critical or it’ll shut our creeks down,” Ford said, adding it could seriously impact the oyster industry and human health. Some public health concerns due to CAFO pollution include harmful bacteria and the avian flu. In an effort to control CAFO pollution, Ford said VES is working on an antibiotic bill in Virginia to give advice to Tyson’s and Perdue’s chicken farmers. VES seeks to educate the farmers on using antibiotics as needed for their chickens and not in a preventative form. CBFS's Tuesday Talk series is offered during each college summer session and brings in professionals from across the Eastern Shore who have careers in conservation and the environment. These events are free and open to the public. Our next Tuesday Talk will be delivered by coastal scientists from the Virginia Coastal Reserve July on 11 at 6:45 p.m. in our education center.

0 Comments

When driving to the water in Greenbackville, the narrow pavement abruptly turns into shells. The entire bayside shore is made up of shells; there’s no sand or dirt, there’s not even a variety of shells, they all look alike.

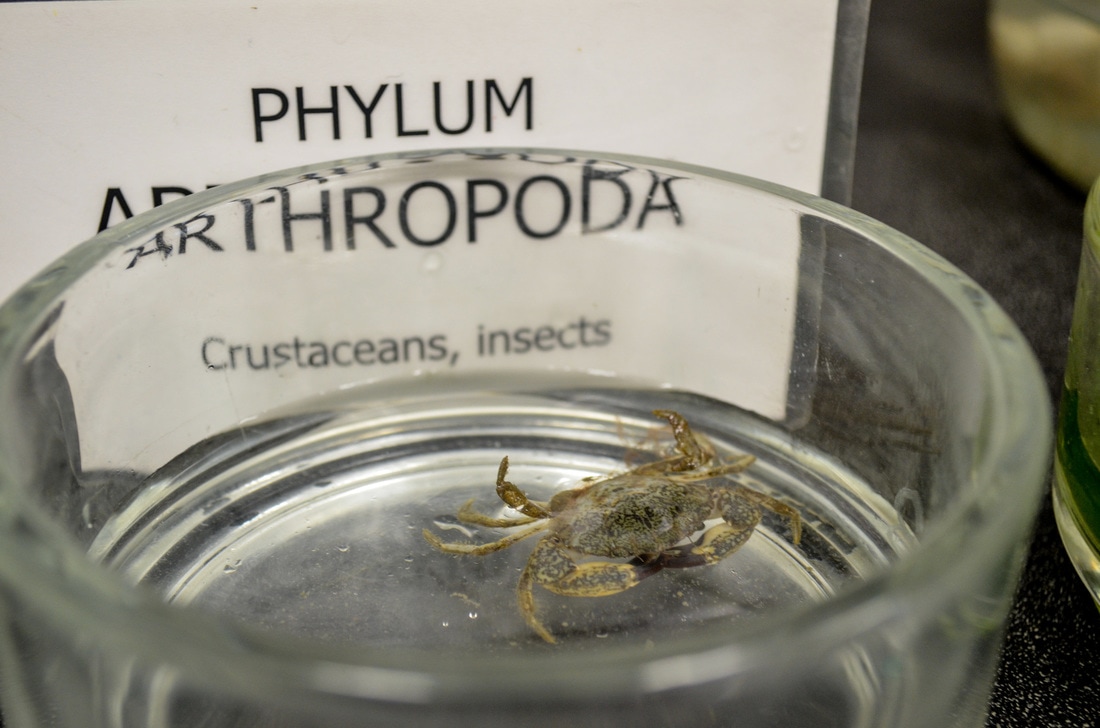

For the most part, these are oyster shells which have washed ashore over the last hundred years or so. This particular area of Greenbackville where CBFS has its Living Shoreline site is formerly known as Franklin City. This village was actually a central location for the oyster industry on the East Coast. As of 1920, Greenbackville had 15 oyster shucking houses up and running. You can still see the skeleton of one out on the bay, standing today as a small, dilapidated platform. It was this location that the Chincoteague watermen would ferry their catch over to Franklin City to be processed at the shucking houses. The oyster shells were discarded into the bay and have been gradually washing up on shore, creating this berm-like feature on the shoreline. After canning the oysters, they were sent north to Philidelphia, Baltimore, and New York City for distribution. The “Chincoteague Oyster” is now a delicacy known across the country. Today, the oyster shell beach serves as an environmental obstacle because it prevents the salt marsh from getting the salt water inundation it needs to thrive. The oyster shells block salt water from entering the salt marsh, causing some of our native species to be outcompeted by invasive plants that thrive in waters with lower salinities. The marsh helps protect people who live along the Greenbackville coast because it acts as a flood barrier and lessens the impact of high tides and storms. In addition to being a sort of buffer zone, the marsh also acts as a filter to the bay by collecting pollution and run off from the roads. Through CBFS’s Living Shoreline project we’re trying to restore the marsh to its natural state. Be sure to join us during our upcoming Community Action Days this summer to learn more about the history of Greenbackville and to participate in these restoration efforts! To get on our volunteer mailing list contact Cortney Weatherby at [email protected]. Panopeus herbstii, also known as the Atlantic mud crab or the black-fingered mud crab, lives in salt marshes and reefs along the East Coast, and is common in the waters of the Chesapeake. Their sandy brown color makes them tough to spot, but look for these small crustaceans in brackish waters underneath rocks or in clumps of seaweed. The crabs have also been known to hide in bottles, cans, and other trash. It’s fortunate that the black-fingered mud crab has been able to adapt to this pollution, however, other types of human impact still pose a threat to the species.

There's two ways you can tell if a crab is a black-fingered mud crab just by looking at its claws. One is to look for dark colored tips on the ends, or "fingers," of its claws, and the other characteristic to look for is a "tooth" on the larger of the crab's two claws. They use this larger claw to hunt their prey. Common prey for the mud crab is the marsh periwinkle snail. Black-fingered mud crabs help maintain healthy snail populations, and this benefits marsh ecosystems because if snail populations get too high, they could destroy the plant life in a wetland. Keep an eye out for these cute crustaceans next time you are near a marsh! Our college ichthyology course kicked off this week with a trawling trip in Queens Sound, and has more exciting excursions lined up to catch and identify a variety of fish. Taught by Dr. Steve Seiler, biology professor at Lock Haven University, Seiler is back at the Field Station for his fifth year teaching the course.  “I take this class as a chance to try and catch as many different kinds of fish as possible,” Seiler said, adding that the Chincoteague Bay area is ideal for diversity in fish species because of saltwater and freshwater habitats. The ichthyology course consists of catching different fish using a variety of field methods such as trawling, longlining, and electrofishing. Students will document and photograph their finds, identify them and take some specimens back to the lab for dissection. Kirsten, junior biology major at Lock Haven University, said she especially looks forward to longlining because she wants to specialize in sharks and deep sea research in her future career. While longlining, the students will be tagging their catches for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).  Victor, junior marine biology major at East Stroudsburg University, said he is most excited for electrofishing. “It looks like a stick, you put it in the water and it sends electricity out that attracts fish and then you catch them with a net,” Victor explained. Victor said his favorite trawling catch of the day were the clearnose skates, which will be dissected in the lab. Dr. Seiler said he hopes this course helps students see and understand how many different species of fish there are. “We know of about 25,000 species [of fish],” Seiler said, “One year we caught about 60 different kinds and we had to work really hard for that,” he said.  Stephen Decatur seventh grade students have been tackling big environmental issues this year including climate change and marine debris in a partnership project with Chincoteague Bay Field Station. In May, these students visited NASA’s Wallops Island as a part of their year-long action project. The students collected 56 pounds of washed up debris including plastic bags, foam pads, and water bottles and learned about how marine debris can negatively impact marine life. Middle school student Markayla acknowledged how important it is to keep beaches clean, as garbage causes harm, even death to mammals. “Sea life will die because they have nothing to keep the water clean,” Markayla said. Markayla added that there are organisms, like oysters, that are essential for maintaining healthy waterways and that pollution can affect the marine life that are already so important to the ocean. Climate change also alters temperatures necessary to maintain the healthy ecosystems that animals need to survive, which can have an effect on the entire food web. Luke, another middle school student, explained that a major contributing factor to climate change is glaciers melting which, in tangent with thermal expansion, causes sea levels to rise. He pointed out that rising sea levels impact both humans and animals alike through habitat displacement. Language arts teacher Michelle Hammond said teaching students about climate change is an incredibly relevant issue that needs to be better addressed in society. “Scientists have collected data and conducted research on climate change proving that it is a global problem,” she stated. Seventh grade student Thorian said he likes to be engaged with the environment and enjoyed the service learning project because he likes to be outside and spends his free time outdoors every day, even when it is raining. Thorian said though despite his class’s efforts, he does not foresee a solution to climate change in the near future. “We drive cars every day and even if everyone recycled it wouldn’t matter because there will always be millions of people who don’t [want to help the environment],” Thorian said. Hammond agreed by saying some day, planet earth could become uninhabitable. She compared society to the Pixar movie “Wall-E,” where humans had to leave earth and robots had to repair all the man-made damage. “This is the world they’re going to inherit and we have to teach them to take care of it,” Hammond said. CBFS’s Education Director Elise Trelegan said she hopes the students realize the magnitude of these environmental issues and see themselves as a part of the solution. “I want to get them excited and passionate about being good stewards of the environment,” she said. Trelegan emphasized that service to the environment does not have to stop at involvement with CBFS. “Students like the ones that we work with at Stephen Decatur have the creativity and capacity to bring new ideas about helping the environment to their social circles to make a positive change," Trelegan said.

Guard Shore serves as a popular spot for local folks to unwind along the coast. It’s a secluded beach-like area with quiet rolling bay waves along the sandy shoreline, but have you ever wondered what all that foam that washes up is? It can spread along the coast in massive heaps or it’s sometimes just a light, bubbly layer over the sand. This mysterious foam is actually just a buildup of protein and other natural sea contents washed ashore. Commonly, decaying algal blooms create this thick sea foam. Large algal blooms decay in the water which will often find its way to the coast. However, the foam forms as the organic matter gets mixed up and moved by the current. You can see for yourself on a smaller scale how seafoam forms if you collected some ocean water in a jar and shook it up. Small bubbles would form on the top because you’d be stirring up all the contents found in the seawater, such as dissolved salts, proteins, dead algae and fats. You shaking up the jar would replicate what happens when the water gets moved by wind and waves. Don’t worry, the foam isn’t a danger to people or the environment. It’s actually a symbol of a productive marine ecosystem. Proteins, fats, salts and other organic matter are naturally found in seawater, plus the unnatural pollutants and artificial matter which can also contribute to the creation of sea foam, are what make the bubbles that can make some waves appear frothy. The waves hit the coast and the froth lingers behind which creates the piles of foam you may see on Guard Shore.

|

About

Everything you need to know about CBFS's educational programs, visiting Chincoteague Island, and more! Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

CHINCOTEAGUE BAY FIELD STATION | 34001 Mill Dam Road | Wallops Island, VA 23337 | (757) 824-5636 | [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed