|

CBFS's Living Shoreline site sits at the forefront of Greenbackville, a coastal community along Chincoteague Bay. Erosion and storm surges plague the field site which is used as an outdoor classroom space for hundreds of middle, high, and undergraduate students each year. During the past year, more than 500 local students from the surrounding communities have participated in action projects at the Living Shoreline, looking at water quality, oyster growth on the Oyster Castles (c), planting Spartina, and removing invasive species. In July students, families, and community members, joined forces with undergraduate students and our staff to review some of the successes of this project. Dr. Sean Cornell of Shippensburg University helped us to kick off the day with an inspirational lecture about the historic significance of the site as well as his experience with the project. Dr. Cornell spoke specifically about his excitement of the oysters that are colonizing the Oyster Castles(c). "This is really fantastic to see. This tells me that our site can support oyster growth," said Cornell to his students during a survey of biodiversity on the castles. CBFS hosts Community Action Days a number of time throughout the year to inspire and educate people about the impacts of climate change and provide the tools and resources for those who live in coastal areas to make positive environmental change. These activities are funded by an EPA grant. CBFS also hosts a collective known as the Living Shoreline Team through their SPARK program which meets once a month to complete stewardship projects at the site. To learn more and get involved in these activities, contact Cortney Weatherby at [email protected].

Conservation biology, an interdisciplinary study including animal identification, data analysis, environmental restoration, politics, GIS and interpersonal communication, wrapped up last week here at the field station. Taught by Dr. Aaron Haines, from Millersville University's biology department, students completed three weeks of field work including a trip to the Nature Conservancy in Oyster, VA, to learn about scallop and eelgrass restoration and snorkeling in eelgrass beds. Mike, Millersville University senior, said his favorite part of the class was the kayaking trips they went on in Shad Landing and Greenbackville. “Every outing we went on had the essential theme of biodiversity,” Mike said, adding that the class looked at factors like the types of grass growing and species of birds present in the two different ecosystems. Haines said biodiversity and species richness are the basis of conservation biology, and examining these two concepts can help determine whether an animal’s population is growing, declining or if it’s healthy. One way the class examined populations was by setting pitfalls. Senior Millersville University student Kelsey said they caught many toads in their pitfalls, and they used the method of mark and re-capture to see if the area was frequently visited by toads. “We caught the toads and put pink dye that solidifies at the tip of its toe,” Kelsey said, “It’s a good method to measure population size and density.” Kelsey mentioned one of her favorite excursions the class went on was an owl and bat survey at night on Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuge. “Something new this year, we have new technology that identifies bats by their calls,” Haines said. Haines said even though the technology isn’t necessarily perfect, it gives the user a fairly accurate identification of bats’ calls. “Three species it identified that could potentially be there were the Eastern red bat, which are pretty common, evening bat and little brown bat, which have a declining population. It’s really cool to know Wallops Island National Wildlife Refuge could potentially have a little brown bat feeding on its property,” Haines said. Millersville University senior, Maddie, said the class taught her how valuable human effort can be in conservation. “The absence or presence of one species can affect an entire ecosystem,” Maddie said. Maddie added that she learned it’s important for people of all backgrounds to be involved in conservation. “You don’t just have to be a biologist in conservation, you can do anything,” she said. Haines said he strived to teach his students not only the scientific aspects of conservation, but how to successfully work with people to meet both the wants and needs of conservationists and the public as well as legal aspects, such as environmental impact statements. “It brought it full circle that scientists need to work with the community and meet their needs while still achieving your goals,” Mike said. In honor of Shark Week, we’ve decided to debunk (or confirm) some shark myths! Sink your teeth into 10 common shark tales that are floating around to see if they’re fact or fiction.

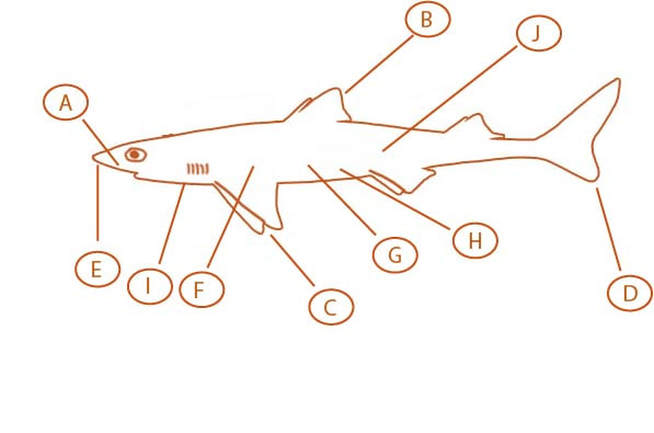

Sharks have no bones Fact Sharks skeletons are made up entirely of cartilage. This helps sharks move around quickly, because cartilage is less dense than bone, and helps keep the shark from sinking to the bottom of the ocean. Sharks commonly attack people unprovoked Fiction Sharks’ diets consist of small fish, and humans look a lot bigger than what they’re interested in eating. The chances of being struck by lightning are actually higher than getting bit by a shark. National Geographic reported you have a 1 in 11 million chance of being killed by shark in your life. However, if you do end up getting bit, sharks will typically realize you are not the food they’re interested in and release their grip quickly. Sharks only live in deep ocean water Fiction Sharks can be found in all depths of the water and some can even be found in brackish water like bays or rivers. Some that are common throughout the Chesapeake Bay include dusky sharks, sand tigers, smooth dogfish and hammerheads. Sharks are in the same family as skates and rays Fact Sharks, skates and rays are all members of the Elasmobrandchii family. To be classified into the Elasmobrandchii family, an animal must have a skeleton made up of cartilage and no bones. All sharks need to swim constantly or they’ll drown Fiction This is true for many shark species, but not all of them. Sharks breathe through their gills, and when water passes over the gill’s membranes, blood vessels pull oxygen out of the water allowing the shark to breathe. However, different species use different methods to force water over their gills. Some sharks, such as bullhead sharks, aren’t active swimmers and can breathe while staying still, but most sharks do need to swim to breathe. The biggest shark is the great white Fiction The biggest shark is the whale shark, which can grow up to 60 feet! The basking shark is the second biggest and the great white is third. The largest great white recorded was 20 feet long. Sharks can sense electromagnetic fields Fact Near the tip of the shark’s nose, its rostrum, there are small pores called ampullae of Lorenzini that gives the shark electroreception. These pores pick up electrical impulses, such as movements or heartbeats of other organisms. This is how sharks find their prey even from far away or in dark, murky waters. Sharks have natural camouflage Fact Countershading helps sharks blend in with their surroundings because they naturally have dark colored tops and light bellies. This helps them hide because if you look down on a shark from the top of the water, it’ll blend in with the darkness and if you look up at it from below, the sun shining on the water will match its bright white underside. Sharks have no predators Fiction Humans kill about 100 million sharks every year, largely because of finning. Finning is an illegal practice that involves cutting off a shark’s dorsal fin to use for cultural or commercial reasons. It’s also been said that shark cartilage can help cure cancer, but there isn’t any substantial evidence to support this claim. While in the womb, some sharks will eat their siblings Fact Multiple shark embryos in utero from different fathers can compete for survival. Typically, the largest pup will devour all of its siblings in the womb except for one. Sharks are one of the ocean’s most famous and intriguing creatures. They easily dominate portrayals of marine life in pop culture from their iconic dorsal fins to their reputations as bloodthirsty predators. Read below about the internal and external anatomy of sharks to learn about what the purpose of each of their fins are, how they hunt their prey and how some of their organ functions differ from humans.

External anatomy: A.External Nares: Near the tip of the shark’s nose, or its rostrum, these are two openings, one on each side, used for sensory activities. Water is taken up through the smaller opening, passes by a sensory membrane and then released through the larger opening. This helps sharks detect blood of prey and determine water quality. B.Dorsal fin: This iconic fin keeps the shark upright and prevents it from turning over in the water. This fin is necessary for sharks to maintain stability, however, they are often sought after in the illegal practice of “finning.” Finning involves removing a shark’s dorsal fin for human use such as making shark fin soup or using it as a home decoration. C.Pectoral fin: This fin helps the shark steer. It acts similar to wings on an airplane. D.Caudal fin: The largest and most powerful fin on the shark’s body, the caudal fin helps keep the shark from floating up without using much energy. E.Ampullae of Lorenzini: This part of the shark uses electroreception. It senses electrical impulses in the water, such as the heartbeat of its prey in the sand, and also allows the shark to read changes in temperature, salinity and water pressure. Internal anatomy: F.Liver: Taking up roughly 80% of the shark’s internal body cavity, the liver is the largest of sharks’ organs. The liver stores energy as dense oil which helps the shark with buoyancy, its ability to float. It also works as a part of the digestive system and helps filter toxins out of the shark’s blood. G.Spleen: A shark’s spleen’s purpose is to create red blood cells. In humans, red blood cells are created in bone marrow, however, sharks have no bones or bone marrow. A shark’s spleen is the main part of its immune system. H.Rectal gland: The rectal gland plays a vital role in osmoregulation, regulating the shark’s salt balance. This helps sharks stay hydrated by excreting high amounts of concentrated salt. I.Heart: Sharks have an S-shaped heart, and it pumps deoxygenated blood through its arteries to the gills where it is oxygenated and distributed through the rest of the body. J.Stomach: Shark stomachs are shaped like a J and are covered with rugae, wrinkles that increase its size digestion and nutrient absorption. Alex Wilke, a coastal scientist with The Nature Conservancy, joined us earlier this week for the third Tuesday Talk of the year. The Nature Conservancy works worldwide to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and people. One of these areas is the barrier island system found on the eastern shore of Virginia.

Known as the Virginia Coastal Reserve (VCR), these barrier and marsh islands are the longest expanse of protected coastal wilderness remaining on the east coast. Within these 45,000 acres of owned and protected land, conservation organizations like The Nature Conservancy work towards land protection, migratory bird conservation, marine restoration, climate resiliency, outreach and education. Wilke’s focus has been on the stewardship and management of migratory and breeding birds that spend time on Virginia’s barrier island system. She studies American Oyster Catchers, Black Skimmers, Terns, Whimbrels, and other shore and migratory birds, which are important to the coastal ecology of the area. Familiar with their behavior, she explained why it was important to protect the islands where they nest. For one, for many of these birds lay their eggs right in the sand. Any large human presence on those beaches would be harmful to the development of those eggs. “They really rely on camouflage, which makes conservation necessary as humans would have an impact,” Wilke said Humans aren’t the only thing these shorebirds have to worry about. Raccoons, crabs, and even coyotes prowl the beaches looking for these nests as a source of food. As mentioned previously, the birds use camouflage to avoid these predators. However, one ground nesting shore bird found here, the Piping Plover, has another unique strategy. When a predator approaches a Piping Plovers nest, the bird will fake a broken wing, flailing about in the sand away from the nest in order to draw the predator away. These birds are an amazing and integral part of Virginia's coastal ecology, and its important to continue protecting and respecting them and their habitat. For ways to get involved, please visit The Nature Conservancy's volunteer page and keep an eye out for information about the Birding and Wildlife Festival in Cape Charles, Virginia. You can find more about this event here. Our final Tuesday Talk of the year will be held on August 8th and will feature presentations from student researchers. Our Sea S.T.A.R. (Students Teaching and Researching) internships are offered to rising high school seniors and gives them hands on experience in marine science every summer. We accept up to eight students and give them opportunities to work in the field on a research project of their choice and chances to lead and educate others with our adult and family programs. Check out what our seven Sea S.T.A.R. interns are up to for their two months at the field station as they study environmental science and share their knowledge with others.

Gabrielle: Due to Gabrielle’s success in her environmental science courses at Indian Creek High School in Gambrills, MD, one of her teachers who worked at CBFS recommended she apply for the Sea S.T.A.R. internship. This is her second time visiting the field station and she looks forward to experiencing more hands-on education while researching how salinity affects the sex of the blue crabs. “I like my environmental science classes. I find it interesting and I like learning about what we can to try and stop what we started or at least slow it down,” Gabrielle said, talking about how she particularly enjoys learning about human impact on the environment and how we can live more sustainably. Heaven: As a junior summer camp counselor at Maryland’s Howard County Conservancy, learning about the environment and spending time outside during summer vacation is expected for Heaven. In her role of a junior camp counselor, Heaven helps teach children ages 3 to 13 about environmental topics like insects, marine life and water quality. Once Heaven graduates high school, she hopes to pursue a career in animal science and her dream job is to be a veterinarian pathologist. For her research project, Heaven will study starlings, an invasive species of birds. “I settled on studying them and their behavior … They’re from Europe and they were brought over because Shakespeare lovers wanted all the birds from his plays here,” she explained. Mikaela: Mikaela visited the field station last year on a field trip with Montgomery Blair High School, in Silver Spring, MD, and learned all about the intertidal zone, sand dune ecology and sustainable marshes. However, as soon as she left, she was excited to come back. “I looked to see if they had an internship here because I really wanted to come back,” Mikaela said. Mikaela enjoys her biology and environmental science classes and is considering pursuing a career in life sciences post-graduation. She looks forward to sharing her knowledge with others about environmental science and ecosystems through the Sea S.T.A.R. internship. For her research project, she partnered up with Emma to study the mortality of horseshoe crabs on Wallops Island. Melody: Future marine biologist Melody, from Wilmington, DE and student at St. Mark’s High School, returned to the field station to kick start her goal of becoming a scientist. “I’ve always been drawn to water and everything that lives in it,” she said, adding she completed an AP environmental science course last year. For her research project, Melody will investigate the different colors of coquina clam shells. “I collect water quality data and I collect a bunch of shells and record their color and then I’m going to try and find a correlation between that,” Melody said. She added that if she cannot find a correlation within her data, she’ll see if local predators play a role in their color. Cameron: Visiting the field station from Barstow, CA, Cameron aspires to be a park or a forest ranger in his future. “I do a lot of community cleanups and I’d like to work in sustainability or environmental preservation,” Cameron said. He added his passion to lessen human impact on nature drives him forward in his environmental activism and future after high school. For his research project, Cameron is looking at different ways to kill phragmites, an invasive species in local marshes, so spartina alterniflora can grow. Cameron added he also enjoys acting as a mentor to the field station’s summer camp kids. “I like working with the kids and helping them learn about different organisms in the ocean,” he said. Emma: As an aspiring animal scientist, Emma was drawn to the Sea S.T.A.R. internship to fulfill her advanced program requirements as a senior at Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring, MD. Emma wants to study either marine biology or pre-veterinarian after she graduates. “I’ve always loved animals and science, they’ve been a constant throughout my whole life,” she said, “There’s so many species we don’t understand. I think it’s interesting how much we don’t know.” For her research, Mikaela and she are looking at the mortality of horseshoe crabs on Wallops Island. Matt: Matt is an ocean and science enthusiast and he’s excited to be at the field station for his first time. A student at Terre Haute South High School in Terre Haute, IN, Matt grew up with a passion for marine life. He’s gone on snorkeling and scuba diving trips in Mexico with his father and maintains his own aquarium at home, which houses a yellow watchman goby, soft corals, a stony coral and clownfish. Matt wants to pursue marine biology after high school and is particularly interested in specializing in coral reefs. For his research, Matt will be analyzing recent trawl catches and compare these findings to former catches and data from a few years ago. “I’m looking at bony fish populations and how factors like pH and salinity change over years,” he said.  Coastal Herpetology students at the field station last session spent a part of their three weeks on NASA’s restricted flight facility searching for snakes to tag and study. Coluber Constrictor, or Black Racer, is a common species of snake found throughout the eastern United States. These snakes are generally black, between three and five feet long, and as their name implies, very fast. Not to worry though, racers are not venomous and will usually flee from humans. However, in dire circumstances, these snakes are not afraid to bite. Just ask Dr. Pablo Delis, the coastal herpetology professor here at the field station. Many Black Racers sank their teeth into Delis as him and his students conducted research on this snake’s population on Wallops Island. The class aimed to measure the snakes, determine their level of health, and tag them. But getting snakes to cooperate with research is no easy task, let alone actually capturing them to get those measurements. Black Racers hunt via sight, meaning they are active during the day and hide in burrows, bushes, or underneath debris during nighttime and cooler weather. So in order to conduct their research, the students set up metal boards throughout the Wallops Island dunes, providing potential shelter for the snakes. Returning to the dunes at dusk, when snakes were likely to be seeking shelter, the students visited each of the boards again to check for Racers. To catch the snakes the students surrounded the board and flipped it suddenly. This allowed Delis a few seconds to grab the surprised snake with his bare hands, hence the bites. The snakes have reason to bite though. Many of the individuals had damaged scales, scratches, and missing tails, among other injuries inflicted by the predators of Wallops Island. According to Delis, the main predators of the black racers are birds, raccoons, and other snakes. Besides their bite, the Racers also possess another defense mechanism in their tail. Delis said that when in grass, this shaking makes a sound similar to that of a rattlesnake’s tail in hopes of warding off hungry predators. After tagging, taking measurements, and noting which board the specimen was found under, the students would release it back underneath the board in hopes the snake would continue to use it as shelter, allowing for future observation. After checking all of the boards, the students decided to use the last few minutes of remaining daylight to check underneath other pieces of debris in the field. Kutztown University student Michayla took advantage of the opportunity and grabbed a large Racer from underneath a piece of driftwood. It was an impressive catch, but it was not without injury, Michayla mentioning that she couldn’t wait to tell her mom she was bit by a snake. While many might not enjoy an evening of chasing snakes, this class had a great time in the field, especially Delis. “Who needs a gym membership when you have Herpetology? You can’t beat running around to catch things that wriggle.” |

About

Everything you need to know about CBFS's educational programs, visiting Chincoteague Island, and more! Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

CHINCOTEAGUE BAY FIELD STATION | 34001 Mill Dam Road | Wallops Island, VA 23337 | (757) 824-5636 | [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed